In a move that has sparked sharp controversy across Kenya, President William Ruto has defended the signing of sweeping amendments to the cybercrime law as necessary in the fight to tame digital crime. The decision comes amid mounting protests and constitutional challenges that threaten to derail the legislation’s rollout.

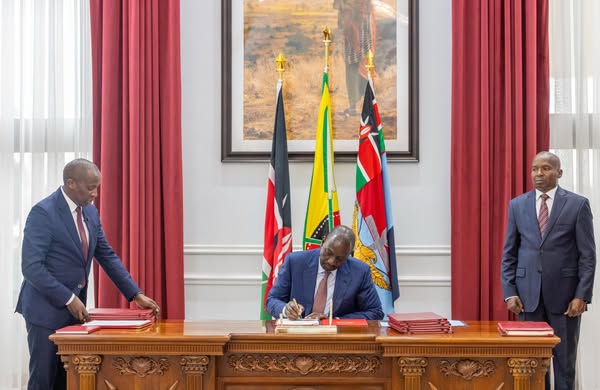

On October 15, 2025, Ruto assented to the Computer Misuse and Cybercrimes (Amendment) Act, 2024 at State House, alongside a package of other reforms. The law significantly expands the government’s powers over online platforms, networks and users—defining new offences, stiffening penalties, and granting regulators sweeping oversight of digital media.

According to official justifications, the amendments seek to fill gaps in Kenya’s capacity to deal with cyber-threats such as identity theft, SIM-swap fraud, online harassment and the use of digital platforms to promote terrorism and extremist cults. But the timing, mode of enactment and scope of the law have triggered a firestorm of criticism.

President Ruto’s Rationale

In his defence, President Ruto framed the law as a timely safeguard for the country’s digital future. He said Kenya must adapt to rising cyber-crimes if it is to protect its growing e-commerce, data-driven services and national infrastructure in the global digital era. Government officials highlight provisions such as criminalising digital conduct that “may lead to suicide”, imposing fines up to KSh 20 million or prison sentences up to 10 years, and empowering the National Computer and Cybercrimes Co-ordination Committee to block or disable websites involved in child pornography, terrorism or illicit cult activities.

Interior Principal Secretary Dr. Raymond Omollo echoed this position, claiming that much of the public debate had been misled by sensationalised media narratives. He insisted the amendments are “progressive” and vital for the integrity of Kenya’s digital transformation under the Bottom-Up Economic Transformation Agenda (BETA).

Fierce Backlash and Legal Challenges

Despite the official narrative, civil society, media organisations and even constitutional bodies have sounded the alarm. Critics argue the law’s definitions are overly broad, its powers too expansive, and its enactment possibly unconstitutional.

The Kenya Human Rights Commission and gospel musician Reuben Kigame have filed a petition at the High Court, challenging the law on grounds that it violates fundamental rights including freedom of expression, privacy and fair administrative action. The court has already issued conservatory orders suspending the enforcement of key clauses—namely Sections 27(1)(b), 27(1)(c) and 27(2)—pending full hearing.

In addition, Kiambu Senator Karungo Thang’wa has publicly raised concerns over the legislative process, alleging that the Senate was bypassed in the bill’s passage, potentially rendering it procedurally defective.

The Big Stakes for Kenya

The conflict over the new cybercrime law isn’t just legal; it may shape Kenya’s digital liberty for years to come. On one hand, supporters say the law will fortify Kenya’s cyber-defence, deter rising online fraud and fortify key infrastructure. On the other hand, detractors warn it hands the Executive unchecked power to censor, surveil and penalise dissent online.

Observers note that the penalty threshold of KSh 20 million or 10 years’ imprisonment for certain online acts is unprecedented in Kenya’s digital legal history. The expansion of power for blocking websites and suspending apps also raises fears of digital suppression, especially in a politically charged pre-election environment.

Leave a Reply